I’m not a big one for Father’s Day, honestly. I try to stay away from social media on that day, step back from the abundance of folks posting loving, well-intentioned odes to their dads, or to those who served as father figures. It’s not jealousy exactly. Just the knowledge of self: there’s no point in striking at scar tissue, regardless of how old it is.

My father was 59 years old when he died of acute alcoholism. He was so far removed from people in his life by that point, he’d been dead over a week before someone thought to check on him. He and my mom split when I was very young, and the other men in my life, guys that tried their best to raise me as a kid as they were caught in their own cyclone of addiction — the majority of those dudes are dead, too. One of cirrhosis, another overdosing on heroin. All these men, fathers staggered throughout my childhood, dying alone in their forties and fifties. Nah, it’s not my favorite holiday.

Last year doctors found tumors on one of the valves of my mother’s heart and cut them off. Fourteen months later, the tumors were back, aggressively, so they gave her a new heart valve. As of today, she’s not responding well to the drugs they’ve given her, and is confused, angry, yelling. Trying to pull her tubes out. Unsure of where she is.

The day after I come home from the ICU, there’s a knock on the front door. It’s been a rough stretch of days, and I’m frazzled and frustrated and weighted down with the seeming relentlessness and brutality of the world as the dogs go wild, barking their heads off at the noise. Before I can even get to the front door, the mail slot opens up, and there’s the bright, begrimed face of my six-year-old neighbor, H.

I open up the door, trying not to laugh at his earnestness, his excitement, and I remind him one more time that the mail slot is for the postal worker to put mail through, not for him to peek into our house.

“I forgot,” he says. He’s standing on our porch, wearing his bike helmet, holding a plastic bag of toys. It looks like he’s dined fastidiously on a plate of dirt for lunch; it’s all over his face.

He asks me if I can play, and I tell him to come back in five minutes. Then we hang out on my porch and play GI Joes and talk about stuff. Superheroes and space guns and Prince of Persia and comic books. The names change, but it’s the same exact shit that I was so enamored with at six.

H. lives at the corner house across the street. Years ago my partner labeled his house “the Screamers,” as in, “Ah, the Screamers are at it again.” H’s mom and her dude fight regularly; he’s been heard more than once calling her a cunt while he stands and fumes out on the sidewalk, huffing cigarettes. Cops have made appearances at the house, and H.’s mom is in rough shape these days, speed-scabs dotting her face. H.’s biological dad is out of the picture because, according to him, “daddy and mommy fought too much and now my dad can’t come to the house.” And we all know what that means.

Poverty and addiction and violence, this holy trifecta of brutality that so often keeps people moored together.

So it’s summer, and H. rides his bike up and down the street with his BB-8 bike helmet and we hang out and play GI Joes in the front yard of my house, or draw with sidewalk chalk, or he’ll ask his mom if he can go in the backyard of Robin and Keith’s house to feed their rabbit.

The parallels are significant. As someone who grew up in a house shot through with violence and addiction, it’s like looking in a mirror when I hang out with this little kid. I remember the constant thread of unease that ran though my own childhood, knowing that any situation could spiral into violence in seconds, over seemingly nothing. I would have loved to have had a safe place to go to, even if it was just a neighbor’s porch.

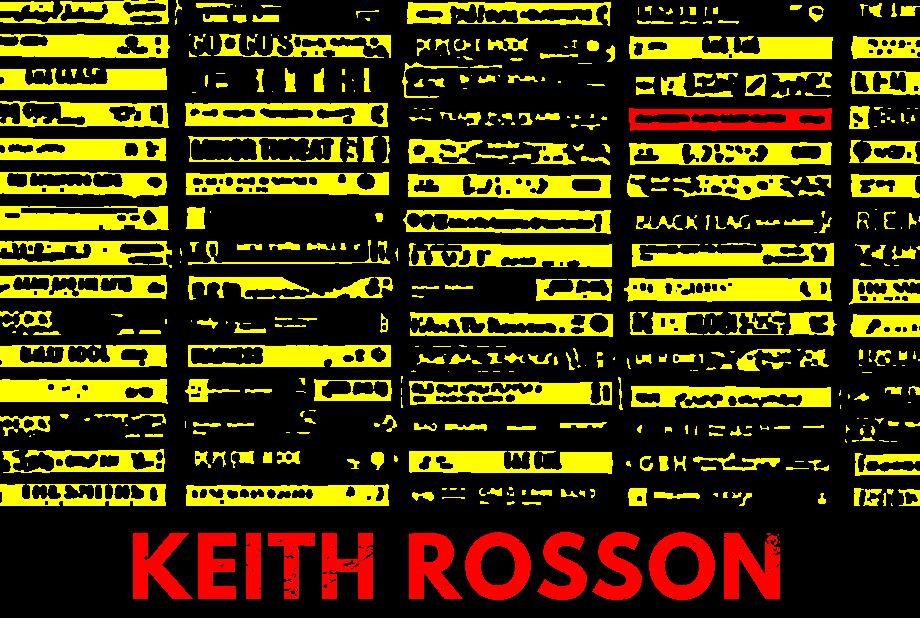

So here’s the thing – you look for the joy inherent, right? You try to find the good in others, you try to be some kind of envoy of non-shittiness. You try to understand that life is hard, hard, hard work for all involved. I mean, that guy that overdosed on heroin, right? I was a teenager when he and my mom split up. He stayed in the house the three of us had rented, and my mom and I moved to an apartment. Later on, that guy would let my friends and I lug all of our shit over to what was my old bedroom so we could practice our terrible, terrible punk songs. Didn’t have to do it, but he did it. He was sober then, and then he wasn’t, and then he died. You know?

And that other guy – sometimes I’ll hear some folk song playing, some blues song, and think Goddamn, you would have liked this so much. In spite of everything, in spite of all of that dark history we share, I still think of him when certain songs come on.

Death takes it all, and we are left laden with memories and the understanding that we’ve been irrevocably carved from our experiences. The people around us – especially when we’re children – are integral in helping form us. Some of those tendencies handed down are things we need to lean away from – I will always, for the rest of my days, struggle with the way I am so quick to anger when I’m afraid – and others? Shit, others we should hold tight.

Sometimes H. is annoying as hell, I’ll admit. “I’m sorry, man,” I’ll tell him sometimes after he’s knocked on the door and the dogs have exploded in a frenzy of excitement. “I’ve got to work for the next couple hours.”

“So maybe in twenty minutes you can play?” he says. Time is still a very abstract concept to him.

“No, but if you’re out at seven, I can play then.”

“Maybe in two hours?”

I laugh. “At seven. Seven o’clock.”

“Okay,” he says, and he walks back to his bike, carrying his plastic bag of busted-ass GI Joe knockoffs and dirt-stained Burger King toys, and I feel a kind of fierceness grip me, like I want nothing bad to happen to this kid anymore, to any kid ever, which we all know is like trying to seize the wind with your hand. Robin and I have decided that we’ll soon begin the arduous, expensive process of navigating the adoption system, but for now, she asks me, isn’t it a good thing that H. has decided, of all the sketchy guys on the street he could be hanging out with – the scrapper guys with their shitty green tattoos on their arms denoting all the time they’ve spent in county lockup, the dudes on the corner selling dope out of their house, the men that go in and out of H.’s own place with clocklike frequency – isn’t it a good thing that he decides that he wants to hang out with me?

It is. But it seems so inconsequential, these minute exchanges with this kid. You want to help someone – the way you wish you had been helped – but you’re not sure how.

But here’s the thing: I’m out on my porch at seven. I’m sitting there, and I’m waiting to see if H is gonna roll up on his bike.

I’ve heard it said that grace is doing a number of small actions well. And sometimes listening to the neighbor kid talk about Prince of Persia while he drinks a glass of water and draws a ninja on the sidewalk is as close as I get to grace these days.